Before we go into the core part of the piece, indulge me for a minute on the future of the newsletter and housekeeping.

First order of business, there will be a renewed focus on the hard topics facing Chinese tech in this newsletter.

Storytime: In Jan, I was casually whining to a writer friend about how my writing was stagnant. I was expecting sympathy. I was expecting praises. Instead, they paused and told me it was because my work had no urgency and avoided the hard questions facing Chinese tech today. I was shook.

The conversation ate at me for days. For someone who prided themselves on intellectual honesty and curiosity, being told that I was optimising for the comfortable rather than the crucial questions was jarring. But there would be no discontent if their comment wasn’t revealing.

They were right. We live in unprecedented and uncertain times, where the FUD is thick, and Chinese tech stocks break new lows every week. I am not answering the biggest questions right now, and I should be. The exchange culminated in a long list of burning questions that fall under the following groupings:

How do investors make money in China in the midst of uncertainty? How do you invest in a socialist capitalist system?

In the slow, steady states of Chinese consumer giants, how will they, if at all, continue to grow?

What is the future of Chinese software?

How are the frontier areas of Chinese tech developing (especially relative to the West)?

I’m excited to explore these topics with you going forward

Second order of business, thank you to everyone who’s filled out the Chinese Characteristics reader survey! Your responses were very helpful and will shape the future of this newsletter (aka more frequent postings for the premium subscribers, shorter pieces with conclusions upfront1). The State of Chinese tech report will be coming soon, but everyone else should have an email from me already - give a shout if you didn’t!

Premium subscribers received the full version of The Chinese Tech Playbook for Winning - Part II last week. Tomorrow they will be receiving a company analysis on Meituan, including my thoughts on the impact from recent platform fee regulations.

Since the response to Part I was positive (share your comments anytime!), here’s Part II about how Meituan’s co-founder Wang Huiwen thinks about the tactical frameworks that go into creating a successful product. The same caveat as last time applies, Wang, like all of us, over-indexes his own experiences. In this case, the focus will be consumer technology and growth during the greenfield mobile era.

How to make a winner

So in the prequel, you’ve found the Big market with a capital Billion. You’re in the market enough to notice the tendrils of change signalling a shift in adoption. You’ve assessed the network effects and found them not high enough to be a winner-takes-all market. Right now, you are getting in during the golden window of opportunity.

The playbook for Wang continues as such (this is your TL:DR):

Being a good last mover - Rather than spend valuable resources on educating the market, there are significant advantages to being the last mover in a developing market.

Find your landing niche - Getting to product-market fit by segmenting the market and targeting the innovator and early adopters through Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning (STP)

Align your core strategy with your core competence - Expanding across different markets and services by building on your core competence

The last mover advantage

Finding the big market is the beginning of its window of opportunity. What now? If a market’s network effects are not exponential, which rarely is, then there are opportunities to being the last mover. From group buying to food delivery to OTA and movie ticketing, Meituan has been a consistent late mover in every category in which they operate. Wang is a big proponent of being the last mover and speaks at length about its benefits:

The market is established - At the abstract level, humans love innovation. But at the concrete level, humans fear innovation. Knowing this fact means that more often than not, it’s easier to wait until another player has educated the market. As the last mover, you don’t need to convince as many users or VCs about what you’re attempting to do. You just have to convince them that what you’re doing is cheaper, faster or better than what's come before.

At the abstract level, humans love innovation, but at the concrete level, humans fear innovation. - Wang Huiwen

The business model is proven - Though there is a market need, it’s often not evident in the beginning what the most viable business model is. Which business model would be superior for the food delivery market — a vertically integrated delivery fleet that provides a superior customer experience or being asset-light and outsourcing delivery to a third party? The ambiguity of viable business models is reduced once they get real-world data. A latecomer can use lessons from failed experiments by others and have a better shot at getting things right the first time.

Rationality through data mindsets - Wang believes that the difference between first-movers and last-movers is one of mindsets. First-movers are visionaries who can see worlds as they want them to be. Last-movers are less prone to blind spots since they benefit from data. The last mover can be more objective in assessing the market than innovators. Wang uses the example that Ele.ma was scrappy and focused on student cities where people already preferred ordering takeout (bottom-up approach). At the same time, Meituan assessed student cities regardless of their current ordering preferences (top-down approach). As a result, it entered Wuhan, a city that, apart from COVID-19 fame, has 1 million students in its 11 million population, making it a good candidate for an early adopter market.1

We can see a case of this happening in real-time with the Community Group Buying trends in 2020. COVID-19 increased the market need for cheaper community-based food delivery, and the success of Xingsheng Optimal illustrated the viability of the CGB business model. Tech giants like Meituan, Pinduoduo and Didi became highly interested in the space and all entered within months. Just like a typical fengkou, it petered out once too many players rushed in and flooded the markets.

Finding your landing niche

It's inevitable as a last-mover that you’ll be faced with a more saturated market. The path to success is not just about counter-positioning but finding a more compelling product for the market.

There’s much convergence in how Wang thinks about product-market fit and western startup literature. The law of early-stage startup success (via Marc Andressen) is:

The only thing that matters is getting to product/market fit. Getting to product/market fit means being in a good market with a product that can satisfy that market. As I alluded to in the last piece, there are debates about whether it is the market that makes the product or the product that creates a market. Given Wang’s interpretation of needs, I would give the following definition for product-market fit:

Product market fit is where the product satisfies the emerging needs of a market. The market needs come first, as they are.

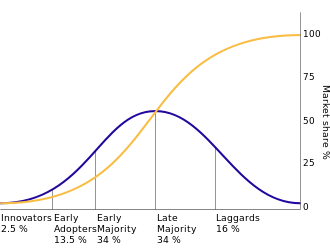

Wang emphasises that finding PMF is a continuous process. Markets are an aggregation of many smaller segments, and as your customer base expands to include more of these segments, the product must evolve too. At each point, the product must fit the scope of the market it is targeting. Taking notes from ‘Crossing the Chasm’ and Diffusion of Innovations, the ‘innovator’ segment of the market should be first. The entry market should be niche but adjacent to a more significant population. It is a landing spot and not the eventual market.

In terms of expansion, it’s advised to go slow with project market fit and then go fast once identified. The product needs to iterate as it tackles each segment, the dominant traits for each category are worth highlighting:

Innovator stage - The customer set has a high openness to new technology (self-described technology enthusiasts). Technology is a central interest in their life or business, and complete feature sets or performance are secondary. They are typically unwilling to pay a lot for new products. Their endorsement means a lot for early adopters. For early adopters, serving the need is already enough. They do not expect the full bells and whistles in the product.

Meituan example: University students living in enclosed campus dorms without kitchen facilities. Their need is to get decent food at school. There are limited options, and they are highly open to trying new technology. They don’t have much demand for timeliness since their time is not valued, and they are probably playing video games anyway.

Meituan had some rough and ready setup back in the day. They had customer service reps write down customers’ information and then call restaurants directly to place orders. There wasn’t online payment, cash was on delivery, and third parties fulfilled the delivery. Not a great experience and the users must want the product (aka food delivered). Only a cornered clientele, like students without access to food, could be willing.

Early adopter stage - Typically visionaries buy a new product early in their life cycle. They are not technologists but are looking for a technology breakthrough for their personal life or business. They are relatively price-insensitive and are highly demanding in terms of product features and performance. They don’t need well-established references to make buying decisions—an important group to win over to signal to the main population. As we move from ‘innovator’ to ‘early adopter’ stage, the key product aspect is better usability. Apple’s contribution to the PC industry is its Graphic User Interface (GUI), which massively lowered the barriers to using the PC.

Meituan example: White-collar workers have a high demand for timeliness and certain quality level for their food, making them a demanding initial market. They were best left once the platform had more robust order taking and delivery capabilities. They were addressed once Meituan had incorporated mobile payment, managed delivery fleets and secured more supplier relationships with mid-range restaurants.

Early majority stage - This customer group comprises the pragmatists who make up the mainstream. They are aware of the passing fad nature of technology trends and therefore want to see substantial ROI and peer references before purchase.

Meituan example: Meituan’s current goal is to deliver anything within a 3km radius. Not just food, but medicine and fruit. This was not something that Meituan was able to do on day one. But much needed to gain widespread adoption for the mainstream.

The crucial challenge for a young business is to find the innovators and the early adopters. Typical innovator consumer sets are likely young folks who are open to new things and also curious to find novel ways to express their identities, sometimes in an effort to counter their parent’s brands.

I’ve come up with a set of rules that describe our reactions to technologies:

Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and just a natural part of the way the world works.

Anything that’s invented between when you’re 15 and 35 is new, exciting and revolutionary, and you can probably get a career in it.

Anything invented after you’re thirty-five is against the natural order of things.

— Douglas Adams, writes in The Salmon of Doubt

Wang also suggests the process of Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning to reduce the cost of finding innovators and early adopters. Segmentation and targeting should be used in tandem to find the initial group of users that would generate the most significant ROI for the current iteration of the product. Given the resource constraints of a typical startup, they cannot serve everyone, and a laddering approach is used with segmentation and targeting to address more prominent markets.

If you enjoyed this - full version behind paywall, yada yada :)

Please do realise there’s a trade-off between more frequent posting, the length and thoughtfulness of each post.