Abridged: Keep product deep-dive

Good product, mad financials

Hi folks, below is an excerpt from the Keep product deep-dive that went out to premium subscribers last week. The full version includes an investment thesis, bear case and financial analysis as well as ~30 minutes of product walkthrough in the Chinese Characteristics Circle community and the full. This week premium subscribers also got an update on CGB, Youzan downsizing, livestreaming regulations and Bilibili.

Background

Keep was started by a university student who wanted to lose weight so he could find a job and an attractive girlfriend. After some false starts, Wang Ning collated information from the internet and lost 15kg in 2014. Everyone he met wanted to know his secret to losing weight, and an app idea was born.

Wang and the team had two pressing issues on their hands — who was the customer, and what were their pain points? In 2014, exercise and sports spending was a nascent market that accounted for 1% of China’s GDP versus 3% in developed economies. Wang didn’t think the people already going to the gym were suited for the app; they would exercise regardless. Instead, they focused on users who didn’t know how to start exercising — that was the blue ocean. The namesake ‘Keep’ is about the persistence needed to keep exercising.

The user demand for beginners is simple: “Appear thin while clothed, appear buff while naked.” They didn’t need a comprehensive exercise app, but just something to get started. A lack of time, space, money, and appropriate company defined these users' pain points. In considering the physical equivalent service in the form of a gym, the beginner had to contend with the following. Average gym membership costs are more than the average wage in Beijing. Finding time and space for going to the gym is a daunting task in a busy and sprawling city. Lastly, people wanted company rather than going to the gym itself.

Before the product launch, the team was already planning how to acquire users efficiently. They lead with a content marketing scheme tactic they called ‘Burying the mines.’ The team went to where the potential users were — on QQ chat forums, on the microblogging site Weibo, on niche interest Douban groups and under Zhihu questions. They wrote elaborate and detailed posts about losing weight with specific exercises. It was worth it to spend a day or two writing a good post for Wang since the goodwill and trust it generated among the community were so strong.

When Keep finally launched, the team followed up with a link to the app, saying more materials were to be found there. The cold start was solved, and the app quickly took off from word of mouth. It took 105 days to reach 1 million users from launch. Suddenly they were the hottest thing in Chinese tech.

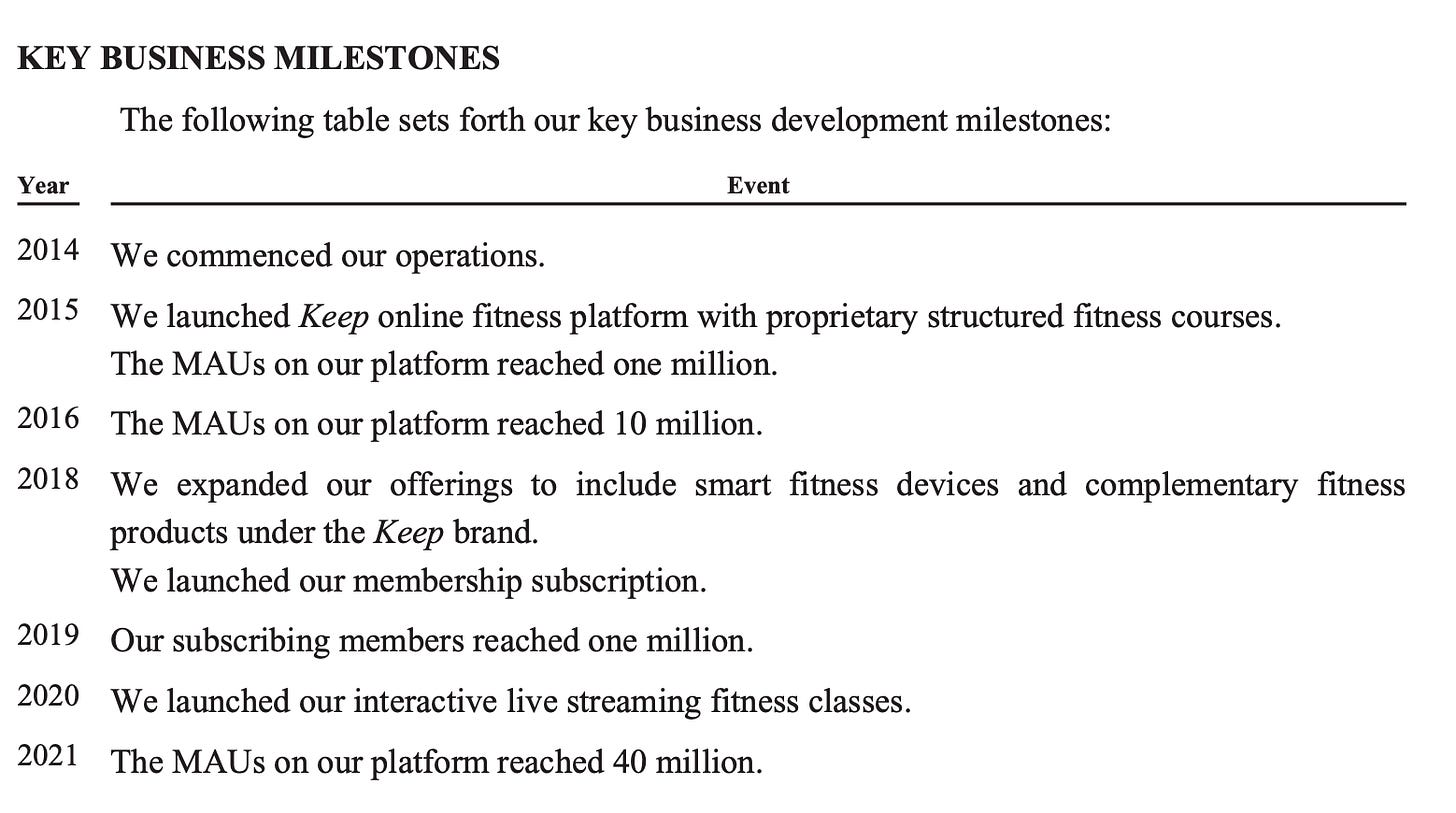

What followed was a whirlwind for the golden child. Keep raised five rounds of funding in a year and grew to 10 million users the following year. Growth was the only logic in those days; they didn’t approach monetisation until 2018.

With 34.4 average MAU in 2021, Keep is now China's biggest fitness app. They are currently monetising via online membership sales, fitness devices, complementary products and advertising. At the time of the IPO in 2022, Keep had raised $614 million from tier-one Chinese VC investors, including GGV Capital, Softbank, Tencent and Hillhouse Capital.

Product philosophy

Wang shared his team’s thinking about the product philosophy of the Keep app as revolving around three principles or product attitude:

More over less - the idea is to satisfy the demands of the many over the needs of the few. Being a mass-market app whose target audience is not sophisticated exercisers, Keep was explicit in making an app that satisfied up to 60–70% of the user demands they faced.

Heavy over light - the product should be ‘heavier’ in content, functionalities, and directives to satisfy the customer's needs. In the shift from the PC era to mobile, the user experience became more immersive, and input became more swipe-based and less reliant on text entry. The product queries lead, as we’ll see below.

Focused over scattered - Keep aimed to position themselves clearly before pursuing other targets. Having a clear aim of the product over being all things straight away. They focused on being a fitness tool first before being a community. People weren’t allowed to post in the community feature without completing an exercise.

While these words were spoken in 2016 before monetisation, it’s clear how much this product thinking is still imbued within the product. There seems to be an emerging tension between being focused by also serving the needs of the many over the few, as we’ll see - this makes for a conflicted app setup.

Product walkthrough

I’ve long felt that the products I’m seeing in Chinese tech are similar to the pitches I’ve heard for so many startups. This is the case for Keep. Keep is a thoughtful fitness app that realises the ultimate consumer stickiness comes from being a holistic service. It internalises the mantra that it’s not products you’re buying but a lifestyle (products, community, and actions included in the price).

Keep’s product has five large sections.

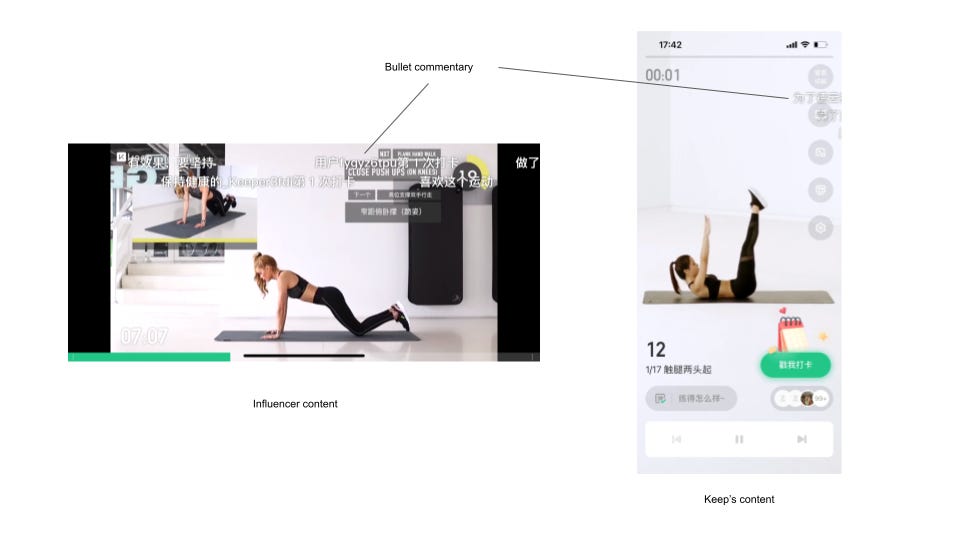

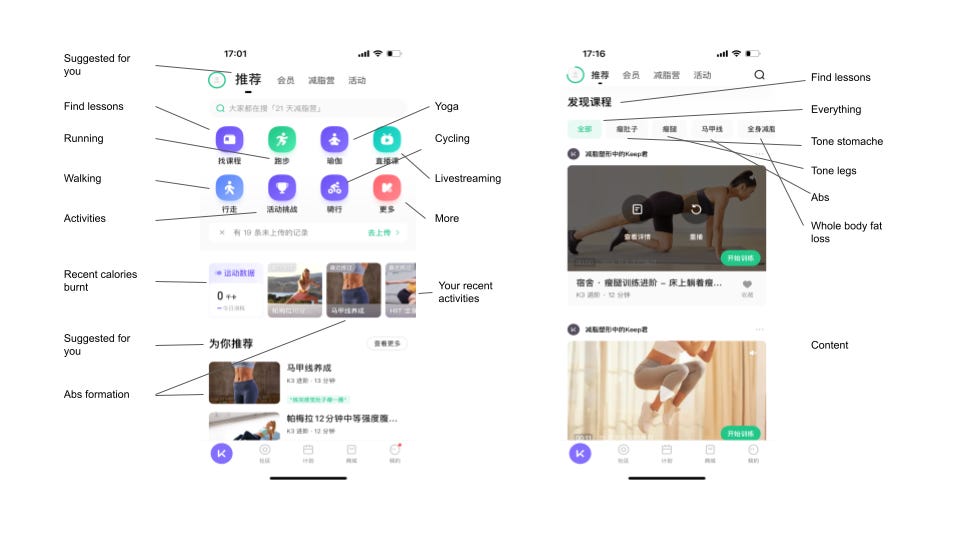

Content - Fitness content is the app's key focus, and Keep adopted a wide range of content in different formats for the end-user. By Dec 2021, there is 10,000 recorded fitness content, proprietary courses (PGC) and influencer content (PUGC) which accounts for 7,600 of total content. There’s also a growing pool of ‘AI-generated workouts' using digitalised images. The formats for the content range from five to 15 minutes exercise to adjustable longer workouts. There are also livestreaming classes and 1:1 classes paying users can access.

Fitness tooling- Keep has also expanded into function-driven tooling of exercises by providing tracking for running and cycling. They incorporate location data, speed and distance travelled, and accompany coaching.

Community - The community section encourages users and influencers to post fitness and weight loss content with links to workouts and pictures of progress or inspirations. Pages are similar to social networking sites.

E-commerce - Keep sells lifestyle products, including wearables, apparel and home exercise equipment. It’s seen as an extension of the brand to consumers.

Offline exercise studios - since 2018, Keep has built offline locations known as Keepland in Beijing (there’s been a series of Shanghai locations shut-down since its peak due to losses). These are typically situated in high traffic downtown areas and offer wearables to Keep members that sync their offline workouts in-app.

The Keep playbook

Keep displays many well-known examples of the consumer tech playbook with a localised twist.

Owning the user through being a continuous service in terms of entertainment, community and products - Keep is a textbook example of a company that increased its product offering to own the user, in this case, from the fitness perspective. Just as Bilibili set out to own the Gen-Z / Millennials users, and Meituan owns urbanites in need of life services. Keep is trying to be the go-to app that turns fitness from a chore to a lifestyle for users. Like the mantra of growth before product, its goal from the outset seems to be focused on attracting traffic rather than monetisation.

In addition to the utility and entertainment, the app also provides unspoken status. Everything helps retain users and encourages them to share to their network to capture additional users. The golden triangle of Chinese tech is complete. (For further reading, see Gamification and Content)

The boundaries between online and offline blurred as the two worlds slowly merged - The ultimate way of owning the user isn’t just in the app metaverse but in real life. Keep is also moving offline. The user can then round off their new identity as ‘Keepers’ by buying Keep-branded fitness equipment, diet meals, and apparel. Go to offline classes in Keepland or join marathons Keep organises. The service for Keepers is the Keeping way of life. (Further reading, see Metaverse)

The golden triangle of utility, social capital and entertainment provides a potent mix. People come for the tools, stay for the social capital, which is stabilised, obscured and legitimised by the entertainment on the platform - Bilibili deep-dive

Enabling the next phase of the search is when information finds the user. Keep’s moat is its vast content library, but making educated users sort through that content to find relevant results quickly leads to fatigue. Like every video platform, the differentiation is in the curation mechanism to avoid user fatigue.

Realise that SaaS is a tricky business and instead pivot to a Peloton-like model to sell hardware and lifestyle goods - Similar to how people don’t like to pay for SaaS, selling personal memberships is also a hard slog. Keep no doubt realised this in 2018 and quickly started to develop its own hardware division.