Happy Chinese New Year everyone! All the best for you and your family in the Year of the Tiger. Today's piece took longer than expected, but hopefully, you'll agree the topic is well worth it. Edit: Part II is here

A few questions for you:

A micro-mobility startup is pitching your firm. They've raised up to $150m already in their seed and Series A and are now raising a $100m series B off a skyrocketing GMV. Does this represent too much capital raised already?

A startup is pitching to the investment committee, and they operate in a space that has seen a few sizable failures and no big winners historically. A partner with 20-plus years of investment experience tells the team that they've seen how this will play out, having invested in something very similar five years prior and lived to regret the decision. Would you still move forward with the investment?

A five-minute grocery delivery startup with locations in major Euoropean capitals announces their moat is their network effect. How do you assess this claim?

The above were all real-life situations that I've experienced while working as a VC. My answers to these questions were coherent but fragmented. I had no great framework behind my thinking, just accumulated Medium thought pieces. But someone had a framework for these questions and used it to build a bona fide Chinese tech giant. Today I want to tell you about how Meituan's co-founder, Wang Huiwen, sees the world.

It is an understatement to say Wang is a credible expert on startup growth. He was Wang Xin's constant co-founder, having gone through the success and failure of Xiaonei and Taofang1 together before they finally hit it big with Meituan. He was there from inception to IPO, handing posts such as head of location-based services, ride-hailing, and R&D. Meituan's reputation as the most battle-hardened tech giant whose management works with robot-level sangfroid is well earned. Despite being underdogs, they emerged victorious from the battle of the thousand Groupons through a combination of clear-headed thoughtfulness and ruthless efficiency. Since then, Meituan has expanded into various new business lines, including hotels, flights, cinema and other offline services. Wang's lectures indicate that while luck played its part in Meituan's eventual success, it was no accident. At the age of 41 in 2020, the billionaire retired. I'm about to summarise a series of lectures Wang gave on product management at Tsinghua University2 in Sep 2020.

I found the series insightful, so much so that I've since changed my framing of investment experiences (and if you were inclined to read the entire series, you can find the English translation at China Playbook and the slightly different Chinese versions here and here). But I also found it slightly lacking in drawing the core linkages between concepts. So my summary is best classified as a remix — all the key elements from the original but reinterpreted.

Last caveat before we begin — Wang over-indexes on consumer technology given his Meituan background. His advice might be less applicable to enterprise software and other deep tech fields.

How to find a winner

Ask a typical western VC or founder about how to start a successful startup, aka winner (successful here being creating a billion-dollar-plus sized company), and you'll get a variant of this answer: Three components go into creating a successful startup: market, product and people. Find a big market and then the right product for the said market, aka product-market fit, and you'll be on your way. Of course, having the right people can get you to a good / great product and hopefully find the product-market fit faster, so that's why it's all about the people.

Different people will quibble about the relative importance of different groups, and some will make a case for Product> Market> People while others will argue for People > Market > Product. The lack of consensus on the relative importance of each factor (especially at different stages of investment) is what makes VC more art than science.

Ask a typical Chinese VC or founder about how to start a successful startup, aka a winner, and you get a slightly different answer — right time, right place and right people (天时地利人和). Similar, but the difference in emphasis is telling.

For Wang, there are three aspects (corresponding roughly to the right place, right time and right people) in creating a winner:

Find a big market - A venture truism is that big markets can sustain big businesses. But the trick is to recognise the emergence of a truly big market created through digitalisation, aggregation and growth before it becomes the consensus.

Understand whether the market is winnable - By understanding the end state and dynamics within a market, a new player can assess the requirements of winning and whether now is the right time to enter.

Be able to do the first and second aspects continuously, keep learning and be lucky - Wang says, remarkably, little about how to be a good founder3 during the lectures apart from noting the key to winning in startup life is to Seek out the hidden truths and patterns then stick to them, regardless of what the public thinks, or be a contrarian. With two core competencies 1) the ability to discover opportunities, and 2) the ability to learn continuously. The remaining 90 per cent is luck.

Or, put another way, are you the right person at the right place at the right time? While Wang doesn't comment too much on becoming a contrarian4, he does spend large sections on market and timing. So let's dive into it.

Find a big market

While it's easy to say that a big market is the first tenet of building a successful tech company, finding one is not without its challenges. Rarely do we find a viable market with no competitors in plain sight. In the age of advanced digital capitalism, we're either looking to enter existing markets or new ones. The most significant opportunities for companies theoretically exist in capturing new markets as they are created after catalytic changes in Political, Economic, Socio-cultural and Technological (PEST) factors. These markets are developing, uncertain and often prone to underestimation.

The history of technology is littered with market size underestimation. They all arise due to an incorrect assessment of a market's needs during a given time window and the pace of market transformation. IBM's former CEO famously predicted that only five people in the world would need a PC.

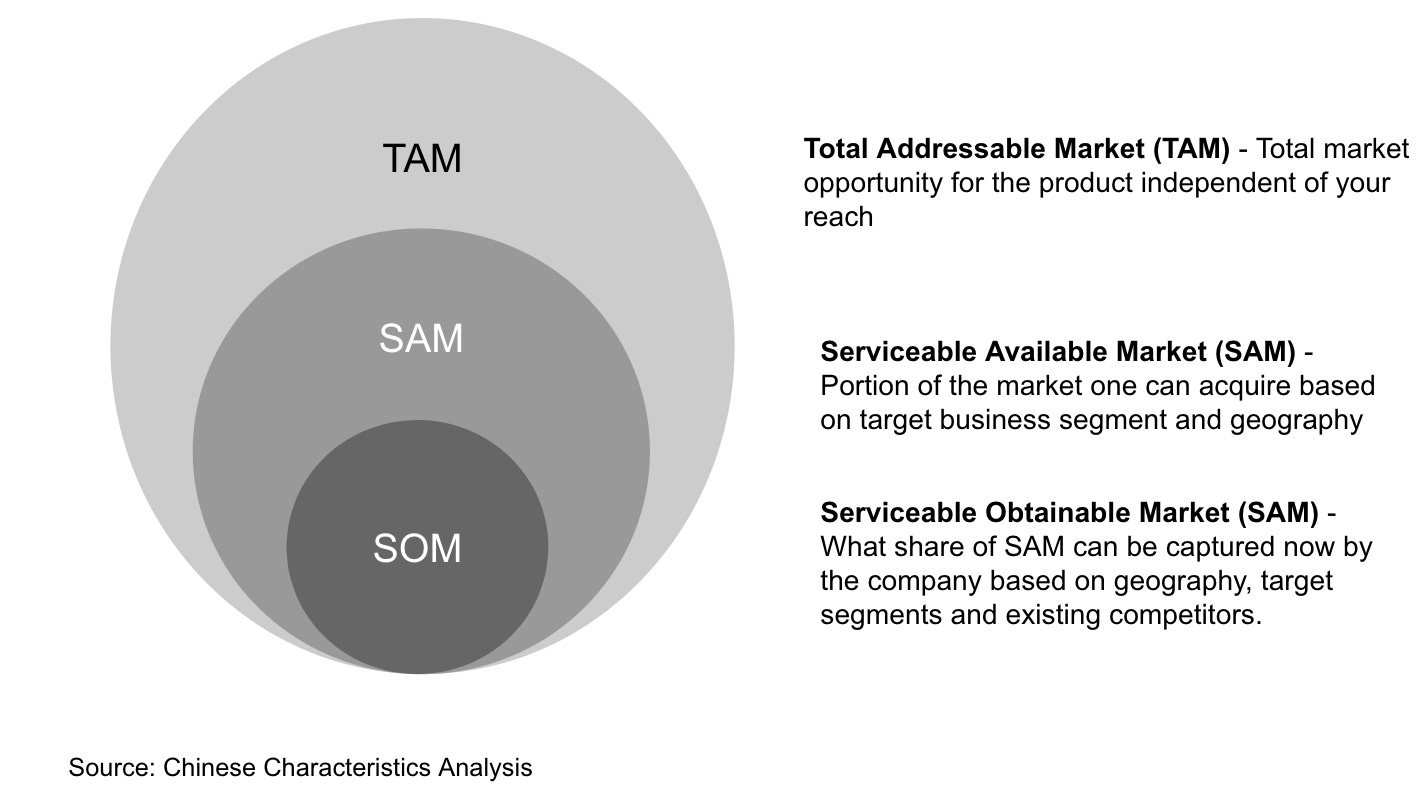

Markets arise out of consumer and enterprise needs. However, commercial manifestations of needs are ever-changing, and the market's evolution moves alongside this. Current technology delivery often limits our ability to envision the full potential size of the market. Therefore, often people mistake the current Serviceable Addressable Market for eventual Total Addressable Market (TAM).

The food delivery industry in China started about 10 years ago, and it has 50-60M orders per day. Coupled with an annual growth rate of 20-30%, it's more or less certain that we'll reach 100M orders a day. - Wang Huiwen

The evolution of needs

Needs should be seen as the demand for new products and services. While they are similar at their core, their manifestations are ever-changing.

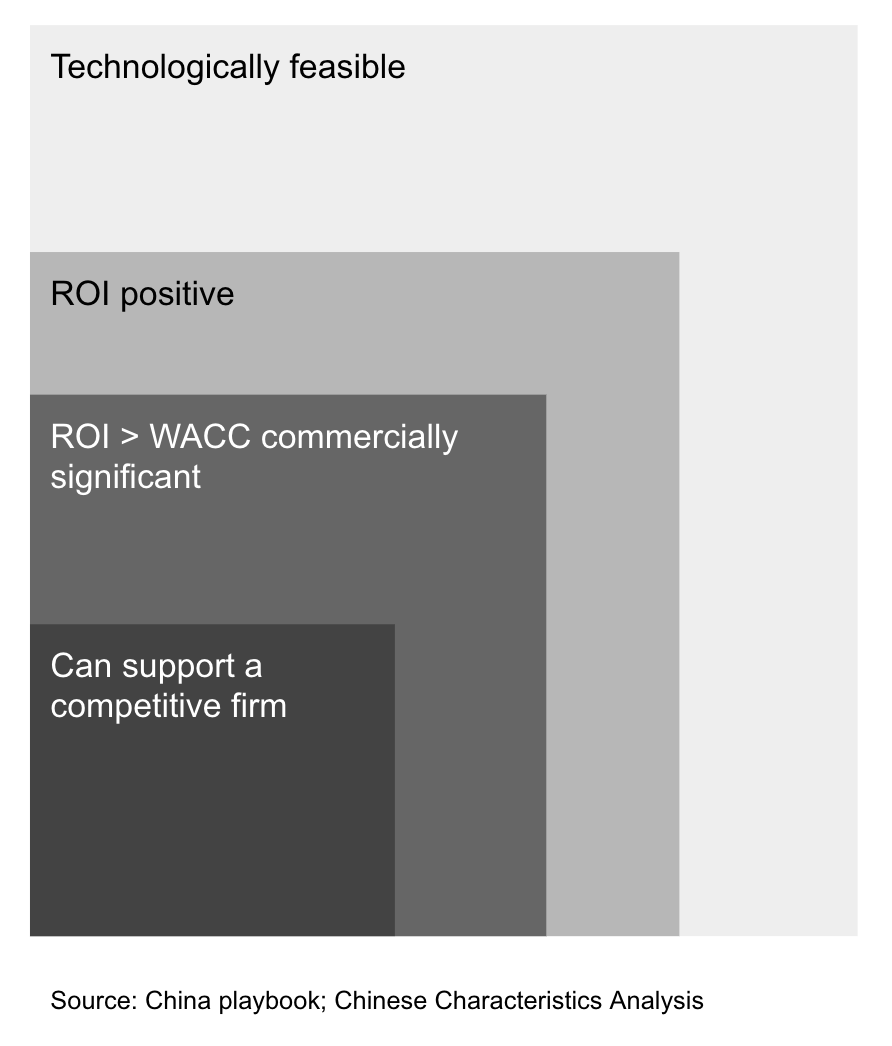

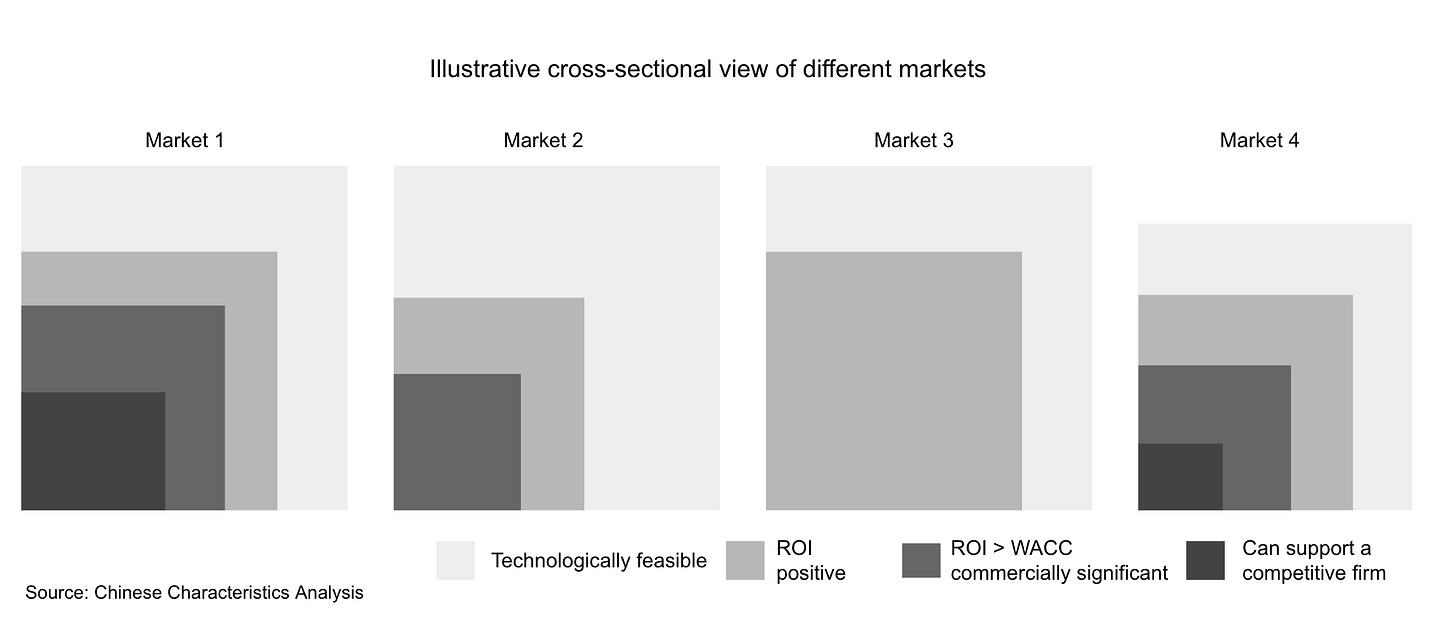

To paraphrase Wang's ideas on needs5:

The number of human needs that can be satisfied is fewer than needs that can't be satisfied - like wanting to live forever is a constant human need, but that need is hard to meet under current market conditions.

Within the set of needs that can be satisfied under our current state of technology, ROI-positive conditions are far less than ROI-negative needs - Clients have needs all the time, but it doesn't always generate a positive return on investment.

Needs that can support a commercial operation are far less than needs that can't. - The level of needs in the market needs to be such that they can justify WACC < ROI.

Lastly, the number of needs that can allow a company to survive competitively is the smallest bucket - Needs should be strong enough to sustain competitors in a marketplace.

Visually, the image below illustrates the layering of needs that Wang's referring to

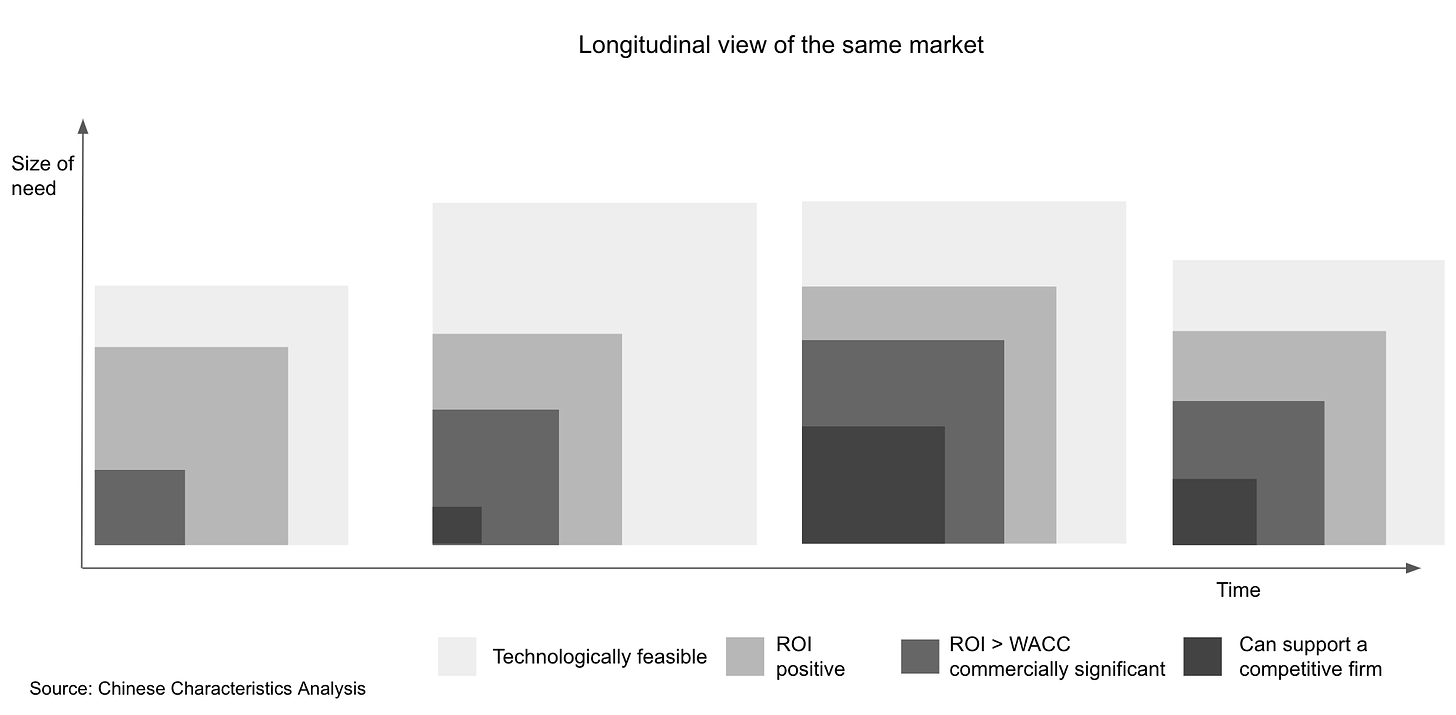

From the standpoint of an individual, their needs manifestation are constantly changing. Wang invokes the notion of Maslow's hierarchy by noting when basic needs such as hunger are unmet, the higher-level needs of altruism and self-expression are not as strong. Therefore, needs are everlasting, but the degree to which they are reflected on the broader community is dependent on the underlying attributes and wealth levels of society at that time.

When people talk about needs, it's usually centred around "I" and not considering the societal infrastructure, wealth level, education level, cultural zeitgeist, etc. Changes in the macro conditions bring changes to a different manifestation of individual needs and, therefore, population needs.

On a human desire level, needs are already set - the need either exists or doesn't. But the intensity, prevalence, and feasibility are affected by many factors. Changes in factors such as technology will mean that the feasibility of satisfying those needs has changed, and in turn, encourage greater intensity of the needs in the general population. Some needs may be amplified by the changes in the social environment, wealth level, or human knowledge, etc.

A key takeaway is to know that TAM is always bigger than what we see today. Still, it requires a suitable business model and technology to make it commercially viable. Wang proposes that to understand the true size of certain TAMs, we should go back to the path of human development, which is the specialisation of labour focused on things we used to do ourselves. To spot the next big market, one must understand how specific needs will become more refined and prominent as people develop. Another indicator of an actual large TAM is if a business is operating profitably and growing fast, it must mean that the demand is super strong. There is an implicit but natural correlation between market size and growth rate.

This is clear to see from how Meituan arose. Wang and the team bet that people will come to see home cooking in the same vein as making one's clothes. It was a historical necessity, but as labour specialised and time became increasingly valuable, it will become a pastime indulged by a minority. This was not common wisdom when Meituan just got started. Wang was discouraged by the market cap of Grubhub, which only had a market cap of $3bn upon their IPO with 200k average daily orders. It was only looking at Ele.ma and their fast growth rates while staying profitable that the Meituan team knew they had something on their hands.

Knowing the total addressable market allows both founders and investors to judge the investment size needed to win the market. A large enough market is worth a large enough investment, and secondary to this, the proportion of investment should be related to the outcome. This throwaway remark is significant because VCs tend to consider investment figures in absolutes rather than as a relative proportion of the opportunity.