I was travelling last week and didn’t manage to get the edition out on time. So here it is this week! Premium subscribers did get an 18-page deep-dive on a very interesting (at least IMO) SaaS company. I’ll be back soon with a look at China’s carbon-neutral tech

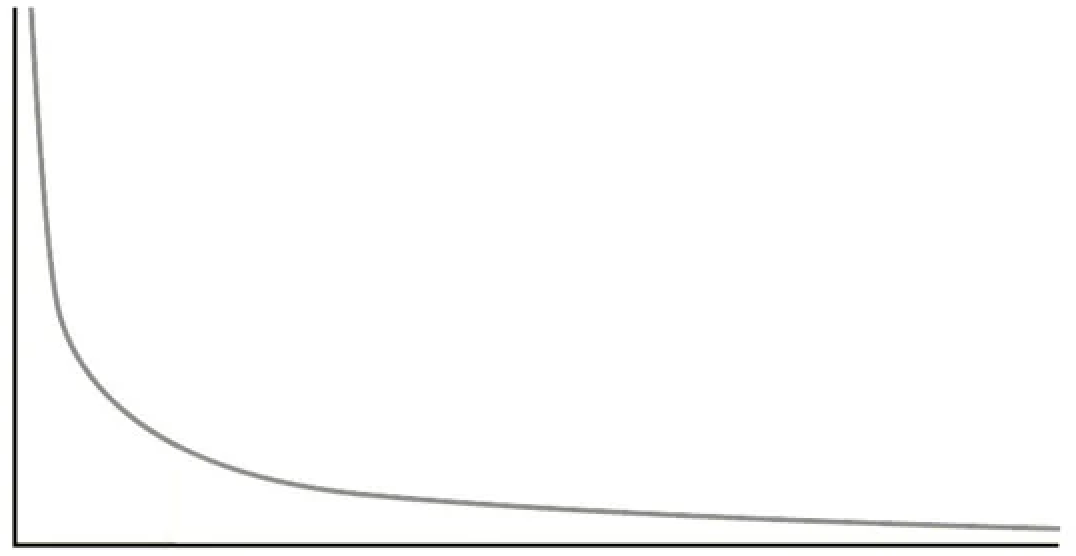

I recently finished The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Art of Disruption by Sebastian Mallaby, a book about the history of venture capital. The title is derived from the asymmetric distribution that runs through much of startup exits and its second derivative, venture capital.

Power law, so called because the winners advance at an accelerating, exponential rate so that they explode upward far more rapidly than in a linear progression - Excerpt from The Power Law

Taking an atypical approach in the current anti-tech climate, it chooses to exalt the shadowy kingmakers of venture capital instead of villainising them. As such, it could be a book that lasts the test of time. Mainly because the victors write history, and VCs have gotten rich off the longest tech boom in history. From Arthur Rock’s backing of the Fairchild Traitorous Eight, to how Don Valentine coaxed wild founders into a deal, to the rise and decline of Kleiner1, the book covers the gamut of the US VC industry. It is thick with personable Midases, their illustrious VC houses and the deals that made them.

Speaking as a Chinese tech aficionado, the book did a poor job covering developments in this part of the world, which is a shame. One chapter was devoted to the subject, and most of it was focused on US-based Sequoia. The other investment behemoth in China, Hillhouse Capital, was barely mentioned. It also lacks what I feel is the flavour of VCs with Chinese Characteristics. So let me have a go at the task.

Have you ever seen a miracle?

There’s a clear divide among the VC mindsets in different geographic regions. The book calls out the difference between the west coast and east coast VCs as the divide between believing in visions versus in the numbers. I’ve seen this myself as a general attitude for European VCs. If I could be so bold as to rank the willingness to believe in visions, it would look something like the following:

US VCs > European VCs

If I were to place Chinese VC on this spectrum, it would be between the two:

US VCs > Chinese VCs > European VCs

The first factor in whether a given region is willing to believe in visions is whether the ecosystem has witnessed extraordinary successes in the past. Without personal proximity to these successes, they've become myths by the time they reach the end-user, where ineptitude and luck are reimagined as roguish foresight. The fabled contract on a napkin is effortless cooperation in action, not some ill-considered future lawsuit. Every detail has been imbued with meaning rather than the result of some happy accident. Of course, the money that flows through the ecosystem from these exits also doesn't hurt.

For either VCs or startups that haven’t personally witnessed these miracles, there is the assumption that they could never reach that level of success. In the absence of this collective belief, numbers are much more tangible. When you witness mundane and somewhat inept (which is to say, ordinary) people achieve unbelievable success, it normalises that such outcomes are available in a way that moves beyond what statistics suggest2. And there’s something in us that wants to believe. The genius of Silicon Valley is to enforce this belief system to become self-fulfilling (hello metaverse).

In the case of Apple, VCs were being told that they should invest simply because others were investing. However circular this logic, it was by no means crazy. The whispering grapevine was sending a message: Apple would be a winner. In the face of that social proof, the objective truth about the skills of Apple’s managers or the quality of its products might be secondary. If Apple was attracting funding, and if its reputation was soaring thanks to well-connected backers, its chances of hiring the best people and securing the best distribution channels were improving, too. Circular logic could be sound logic. - Excerpt from The Power Law

China has replicated this mindset through its 30 years of unprecedented growth, which has inspired a belief in the future's potential in a way that is unparalleled at this scale. That being said, the flip side of this growth is a deep streak of instability that drives a particular breed of a scarcity mindset. How long can this trend last before the next thing comes along? Will I be able to take advantage of the next thing? Will the regulators get involved? The quick turn from optimism to cynicism and back again sometimes creates whiplash. In Chinese VC, we see both the stamina to go big or go home and the tendency to feel like the sky could fall at any moment.

Go your own way

Silicon Valley’s early development could be divided into three phases. At first, the capital was scarce, investors few, and entrepreneurs had trouble raising money: this described China in the late 1990s, at the time of Lin’s Alibaba investment. Next, money flowed in, the tally of venture capitalists shot up, and startups multiplied both in numbers and in ambition: this was analogous to China around 2010. Finally, as the competition among startups became hectic and costly, the Valley’s venture capitalists performed a coordinating function. They brokered takeovers, encouraged mergers, and steered entrepreneurs into areas that were not already swamped; as the super-connectors in the network, they shaped a decentralized production system. This was the final threshold that China had to cross. By 2015, it would have done so. - Excerpt from the The Power Law

Venture capital is a young industry in China. As the book recounts, the Chinese venture capital industry was decidedly American in its origins — from the source of the money to the background of the first hires. In this, it is not too different from how China leveraged FDI to grow many of its industries. The mid-2000s saw the arrival of Qiming Ventures, Capital Today, Hillhouse Capital and Sequoia China. Lacking its own foundations, with limited oversight from the government and swaths of blue ocean market space, various Copy-to-China fengkous and Battle Royales defined much of the 2010s.

Consumer tech has surpassed the West in its business model innovations in many ways. We’re now in the Copy-From-China era3. However, in uncertain territories such as B2B, there’s a lack of institutional taste for a uniquely Chinese business model. A standard Chinese VC question to SaaS startups is ‘what’s your US or European startup equivalent?’. Domestic excitement about the Metaverse and PLG in the last six months were all drawn from overseas trends.

Chinese VCs also overfit on their previous successes. After speaking to a few B2B Chinese VCs and even more B2B founders, the message is the same — Chinese VCs as a group don’t get software growth yet. After growing up in the consumer tech bonanza with the playbook of grabbing market share through burning money and then monetising by raising prices. VCs are unclear about how to operate in the brave new world of hard tech and B2B sales. The almost fanatic devotion to tracking DAU and MAU makes them overlook the attention to service needed in B2B sectors.

The direction of travel for Chinese VCs looks similar to that of the West, from a small cottage industry to professionalised platforms. Sequoia and Hillhouse Capital are becoming multi-stage investors that supply startup capital and platform building resources from inception to IPO. It seems like whatever time zone I talk to, the investor’s complaints (until very recently) were all the same: “Valuations are crazy” and “I don’t know how anyone can make money in this market.” One way or another, the power law means there's less of the middle, be it investors or startups. The shocks to the secondary markets have also hit the VCs market, and there’s been much hand wringing amongst the USD-denominated Chinese funds about the potential future of their exits.4

The power law is eating the world

A founder who runs a chain of VC-backed bakery stores (you read that right) made the astute observation that the power laws automatically take effect with venture capital injection into any industry. I think about that often.

The growth of the power law and the growth of venture capital does indeed go hand in hand. The injection of VC money and subsequent digitalisation of the world has lowered friction, and a lower barrier to entry has made the impact of the power law more apparent.

As individuals, VCs thrive on earned serendipity. As a group, their emergent properties are being multipliers and accelerators to innovation and, occasionally, hubris. This has been more apparent in China than anywhere else. The convenience of paying with face scans at checkouts does not overshadow the mounting losses and casualties each fengkou creates.

VCs as individuals can stumble sideways into lucky fortunes: chance and serendipity and the mere fact of being in the venture game can matter more than diligence or foresight. At the same time, venture capital as a system is a formidable engine of progress—more so than is frequently acknowledged. - Excerpt from The Power Law

The Power Law never questioned whether we should accept the power law as a new reality. It assumes it already is. It takes it as a matter of physics rather than a social science and economics construction. By virtue of state direction, Chinese VC will diverge slightly from their Western counterparts in adopting this new order. The government’s rhetoric of ‘disorderly expansion of capital’ is vague, but it points out that capital and the bifurcated world it brings can not all be a good thing.

China’s somewhat centrist tone — that capitalism and the free market are a power factor of growth and should be respected and governed to harness the most equitable outcome — seems quaint in a world being eaten by the power law. It asks venture capital to direct their arsenal at deep tech that would improve the country’s technology frontier rather than 15-minute grocerie deliveries. Does this lead to a better median outcome for its citizens? Can this co-exist easily with ecosystems that have given wholeheartedly to the power law reality? Is the role of government somewhat at odds with the power law? As always, I ask questions to which I have no answers to yet. But I’ll keep you posted on when I find out.

TLDR singularly big rainmaker with bets and personalities that were ahead of its time

You would not believe the number of founders who started something because their friend “Dave” started something, and “Dave”’s definitely not as smart as them.

In the form of livestream monetisation and community group buying

Chinese VC funds fall into two categories, RMB-denominated and USD-denominated funds. RMB-denominated funds’ investments list on the domestic exchange, while the USD-denominated funds list on the Nasdaq. Thus, USD-denominated funds also tend to invest in the type of swashbuckling moonshot companies that get listed on the Nasdaq.

Interesting, yet you would need to understand the political impact on VC behaviour. You will be surprised to find out this plays huge impact and differentiates US VC with China VC