What I talk about when I talk about Chinese tech

On the enablers of what makes Chinese tech trends take off

Back when I was a bright-eyed youth, I did a masters in International Development because (and say it with me here) I wanted to make the world a better place. International Development is the study of why some developing countries become rich while others stay poor. My biggest takeaways that year was how much institutions mattered in developing a country and the importance of context specificity for any policy to work.

The early 2010s were a point of deep reflection for the international development community as they pondered the Washington Consensus’ failure in spurring growth. Wholesale import of policies such as free trade, capital control and democratic elections to developing countries didn't result in an unleashing of productivity and growth. Often the catastrophic opposite. One explanation is that institutions matter as a determinant of change, and blindly applying cookie-cutter growth policies without accounting for local context was a recipe for disaster.

Douglas North defined institutions as "the rules of the game in a society, or, more formally, the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction." The power of traditional institutions such as the media and government has been eroded as technology platforms set the new rules of play. In spite of their protests, technology platforms have become the new institutions. Their successes and failures will be path-dependent on the prior tech and non-tech institutional frameworks they’ve evolved from.

Over the last week, I listened to Another Podcast's episode on 'Two Europeans talk about China' and read your feedback in the reader's survey. One of the most consistent questions that arose was 'what are the latest trends / hottest under-the-radar startups in China, and how can we apply that learning in the West?'. This framing reveals a bias that tech trends and their applications are as universal as the plug-and-play fiscal policies the IMF once endorsed.

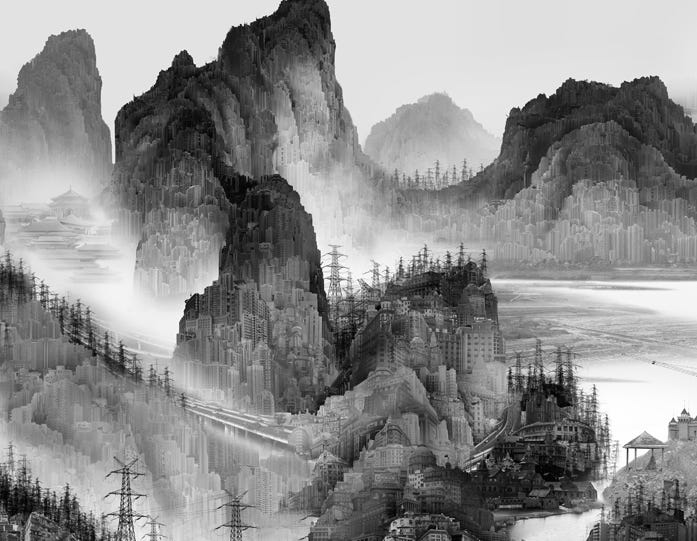

Chinese tech is a loaded term. The very fact that we have to say 'Chinese' tech rather than tech demotes its otherness. So what does a place of origin signify? The differences in market conditions, political context and most importantly, the development stage of the country. A key theme that runs through Chinese tech is that as a developing country with under-developed institutions, technology isn't augmenting existing institutions, but creating them. Combining all of these factors means that China's tech ecosystem is neither ahead nor behind that of the west, it is a parallel world.

The parallel nature means a fundamental rethinking of foundational principles, including:

Copying is not wrong; in fact, it shows the founder's pursuing a de-risked business model.

There are no unscalable resources, especially when labour is cheap.

Making money is the only core competence of a Chinese tech company.

What does that mean when we look at whether a business model that is hot in China would work elsewhere in the world?

We would need to think about China’s enabling conditions (both technical and non-technical) for its success and how much of that can be easily translated. A prior example is that Chinese tech copied extensively from West tech in the beginning, but the players that survived did so through extensive localisation.

Let's go through a few examples in the form of livestreaming commerce and online education.

Livestreaming e-commerce

If you haven't read my previous article on Chinese livestreaming e-commerce, now's the time. Livestreaming's enabling factors in China include:

Embedded digital payment system - which allows users to checkout in 3 clicks while watching the livestream. But China's leapfrog to digital payment was due to a shortage of credit systems in the 2000s. Nowadays, digital wallets are ubiquitous.

Robust logistics chain for next day delivery and returns - There are sizable logistics players whose capacity has been built-up from the e-commerce wars between Alibaba, JD and Pinduoduo over the years.

The ecosystem of Multi-Channel Networks (MCNs) cultivates livestreaming talent - MCNs are essentially modern-day talent agencies for creators. They do a lot of the legwork in identifying up-and-coming creators, supporting them and co-ordinating their partnerships with brands.

Fandom culture - there's a strong sense of fandom in China for idols (similar to Japan and Korea, think BTS army level of fervour). Heightened degree of parasocial relationships means that fans are often happy to support their idols through monetary donations. I suggest the documentary 'People's Republic of Desire' for a case study.

These enabling factors mean:

Frictionless in-app check-out process while watching the livestream - Any friction for the consumer as they move through product awareness, consideration and purchase mean drop off. The more one can reduce this friction, the easier the whole process flows.

A robust supply of livestreamers who know how to communicate to the medium - selling a product on a livestream to sycophantic live comments is a skill. The most successful livestreamers in China present bombastic personalities alongside established sales chops. These individuals were trained and supported by MCNs, who can nurture enough talent to meet the brands' demand for effective livestreamers.

A superior online buying experience for selected products- livestreaming enables a more interactive selling experience which mimics aspects of in-person retailing. Livestreaming hosts answer questions about the product and highlight their usage in real-time. This method works well for apparel and makeup as well as other fast-moving consumer goods.

Overall, livestream e-commerce shortens the awareness to purchase cycle. It doesn't magically make people believe in e-commerce. Everything else needs to work as a foundational piece before livestreaming can elevate it.

Online edTech

Another 2020 Chinese tech trend has been online K-12 education, with the top two unicorns of Zuoyebang (作业帮) and Yuanfudao (猿辅导) completing billions in fundraises throughout 2020. Publicly-listed Genshuxue (跟谁学) and Xueersi (学而思) reached all-time stock price highs in 2020.

The business models are straight forward - paid packages for online lessons with brand name teachers. ‘Brand name’ as they often have excellent educational backgrounds (a degree from Peking or Tsinghua university is the norm) as well as scores of teaching accolades. Students can get additional modules such as one-to-one text-based tutoring lessons, question banks and mental arithmetic practice apps. I'll go into a fuller deep-dive at a later date.

Online edTech's enabling factors in China include:

A strong cultural emphasis on education - call it the Confucian value system, but culturally there is a strong emphasis on education. It is both a status and morality signifier as well as the pathway to a better life. Historically, this was codified through the imperial exams and has been re-enforced in modern China with the Gaokao. This means getting an education has often been an end in itself as well as a means to an end. Parents are extremely willing to pay for educational products

An education system based on test-taking and rote memorisation - The reality of a nation with 1.4bn people is that every year, 10m pupils will sit for the draconian national college entrance exams (colloquially known as Gaokao). Given the sheer number of candidates for selection and the limited resources available to examine each as people, universities’ entrance is mostly score based (though rules do include limited extra points for extra-curricular activities). Every point accumulated on the Gaokao tests matters, it’s the difference between a first-tier university or a mediocre one. As such, this incentivises an education system that favours test-taking and rote memorisation. Understanding the concept thoroughly means answering every variant of question that can be asked on that concept. That’s a lot of time spent going over questions with guidance from tutors.

Limited availability of good teachers in China - While teachers are respected more in China than the west, their quality varies hugely across regions. Like most resources, the lower-tier cities often do not have access to the best quality teachers.

The edTech offerings are digitisation of the existing after school cram culture and a manifestation of the prevalent status anxieties. In the Red Queen world that is China, if everyone else in your high school is taking cram courses, you lose by not taking part. I think as network effects taper off at scale, the loss-prevention effects kick in. Facebook's not missing out on you joining as much as you're missing out on the social capital that is being exchanged on the platform. Same thing for edTech platforms at scale. Though the missing social capital translates much more easily into real-world prestige and access in the form of entrance to a good university.

The fact of the matter is that education was always a hot market in China; putting the technology wrapper around the content and moving it online did not change the beast’s nature.

All in all, my advice for entrepreneurs looking to capitalise on Chinese tech trends would be to assess them through the following questions:

Do I exist in a tech ecosystem with similar enablers as the Chinese tech ecosystem? If not, should I focus on building out the enablers instead?

Is there already learnt behaviour in an offline setting that can be readily digitalised? How much education does the market need?

While there is always a trust leap for a new online experience, how can I bridge the trust gap?

I think there’s plenty to learn from Chinese tech, but going through this list will help you avoid the obvious mistakes. As Chinese tech entrepreneurs are fond of saying, you need to find your 'Fengkou’ 风口 aka window of opportunity.

A few last thoughts on Chinese tech. I believe it has shown a more obvious world of tech-enabled institution creation. They are also often held accountable in China as institutions rather than tech companies.

I think it needs to be asked who's 'we' when we talk about Chinese tech. The podcast talk from the perspective of Europeans, with the logic that western tech companies will be the first to adopt trends from Chinese tech and then the rest of the world through them. But I think the true beneficiaries of Chinese tech's innovations are other developing countries also embarking on their own journey of technology-enabled institution building. We’re seeing Grab or SEA in South-East Asia or Rappi in South America all creating super apps and digital wallets for their underbanked population. Chinese tech's innovations are going to profoundly shape the lives of the next billion as they come online.

Some housekeeping from the reader survey: While I asked about your view on adverts, this newsletter does not currently have any advertising. If I do choose to take on any, it will be clearly labelled and will not influence the content.

For the premium paid version I am offering the following:

Monthly deep-dive into Chinese tech (both public and private) companies, and the learnings they offer for startup operators, private market investors and public market investors

Unique access to Chinese tech companies in the form of interviews

Opinions on who I think will be the losers and winners for each trend.

Community on the Chinese Characteristics Circle community

What I'm not offering:

Professional investment advice (duh!)

Regular English translation for Chinese articles

Analysis of what the CCP is thinking. Government policy will always be a background influence on Chinese tech, but this is not my expertise.

Premium subscribers will be getting my teardown on Kuaishou’s IPO this week

Certainly agree on the education part. I'm curious what the gov. thought about rise of ed-tech. The rise of after-school tutorial/online tutorials etc. certainly hints that public education is terrible. Not good for the gov's face. Will the gov. see ed-tech as a threat?

One of the cool patterns I've noticed on Douyin are the rural live-streamers. I watched a Mongolian business owner sell dried beef goods via livestream while playing traditional Mongolian music in the background in rural Inner Mongolia.

Per your essay, I definitely get the "creating economic infrastructure / institutions" framework by strengthening rural economies via livestream tech. It's definitely something I wish the US capitalized on more in its rural areas.