Reflections of an ex Chinese tech equity analyst

Guest post by Leon Lin of Avoid Boring People

Hi folks! I’m back from break and excited for the next year of Chinese Characteristics. Today is a guest post that didn’t manage to make it out during my break from the excellent Leon Lin. Leon writes a finance and tech newsletter called Avoid Boring People, based on his experiences in both industries. In a previous life, Leon was an equity analyst covering Chinese internet equities and is kind enough to share his reflections on that experience.

Also for those of you who wanted to know how to get onto the premium subscribers list, hit the button below. Watch-out for the long-overdue goodies (Taobao walkthrough and Xiaomi deep-dive).

I used to work at a long/short fundamental hedge fund1, and half of my time was spent covering China internet stocks, pitching them to my portfolio manager as investment opportunities pre 2019. Today I wanted to go over three things I wish I’d known, and two case studies. Also, these are just my opinions, happy to hear where people might disagree (find Leon on Twitter at @Leonlinsx or in the Chinese Characteristics Circle Community).

Things I wish I’d known

1. What were table stakes in the investment process versus actual alpha insights

I’ve written a post on the “research stack” for fundamental investors before, with the takeaway graphic below. As a fundamental investor, you’d likely be using many of the companies below to get more data on the company you were interested in.

For example, you would look at Reddit reviews, use Bamsec to get financial data, pull sell-side data via Visible alpha, speak to company management at an investor conference, chat with some industry experts on GLG, and get credit card data from Second measure. This would go into your financial model estimating what the company performance in the future could be like

The problem is that given that most of these are widely known, none of them really give you an investment edge anymore2. They’re table stakes, both for the US and for China investing.

I wish I’d known what the equivalent was for China when starting out, as I’d have saved a significant amount of time, effort, and money in getting data. For example, Ridgetop for industry experts, Sandalwood for data, or even the right WeChat groups to join for public discussions.

The problem in not having the local equivalents was then you’d end up relying more heavily on sell-side equity research3 that covered the company. Sell-side would usually be in closer contact with company management, especially around the IPO and first few quarters4. And while the sell-side people are nice and all, taking their opinions wholesale is you not doing your job.

In comparison to US investing, the above sources were less well known, taking more effort to discover. And even after finding a source, becoming convinced of the data quality was also a hurdle you had to overcome. You’d be able to get a few more confirming sources if looking at a US name, compared to a China name.

Importantly, it doesn’t matter if you find a good source of data, if that information never gets spread out eventually. You make money by front running other investors on good ideas, not by hoarding good information indefinitely.

In other words, for US investing, you could find some data to make your case, and then use that data to convince others of your thesis. For China investing though, you’d face more questions and have a higher bar to clear before people believed in your thesis.

2. Only a few things matter for each name, and probably even fewer than you think

Chinese names tended to have more complicated relationships, even after accounting for the holding company structure5. Many would usually be backed by one of the three big internet companies at that time (Tencent, Alibaba, Baidu - Lillian note: more on this dynamic on The Shadow Investment Wars Between Alibaba and Tencent ), who would be implicit supporters of their IPOs6. You’d spend time wondering if company A would do something negatively affecting company B, which had company C as a mutual large shareholder.

With multiple business lines and varying incentives among their shareholders, it got difficult to figure out what moved the stock. When I started I was building more complicated models with many line items to build up to a more “precise” EPS. Over time I learnt that the model was a commodity, and it was more important to figure out what the investor community had concerns over.

For example, nobody really cares about the risks of the holding structure, stock-based compensation, or the quality of the accounting numbers, despite what the movies might have you think7. In China Internet coverage overwhelmingly people cared about growth, being willing to be paying high earnings multiples for the exposure, which for the most part has worked out.

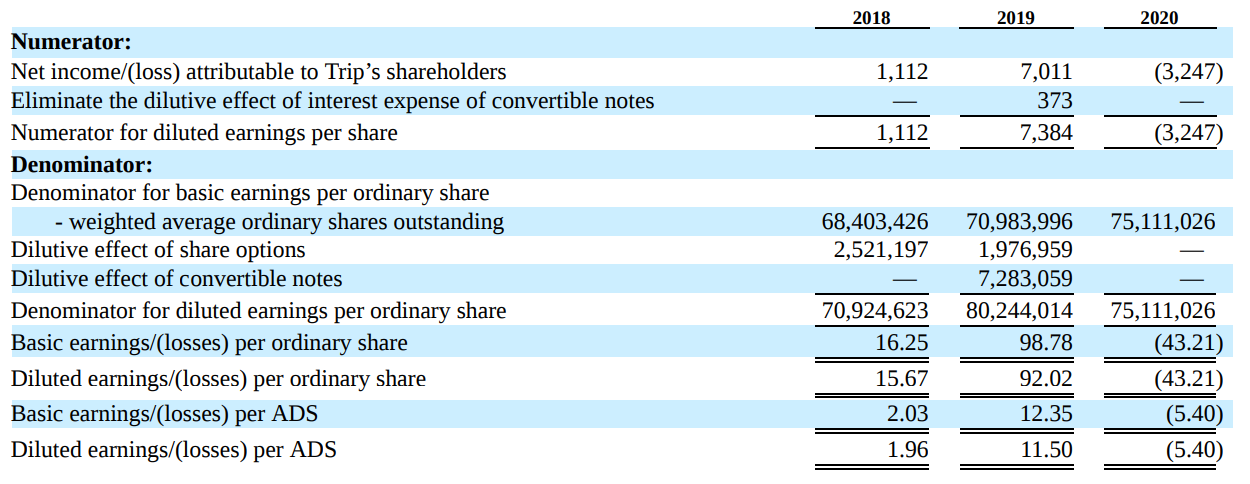

For another more granular example, CTrip (now Trip.com) has always had a large number of convertible notes outstanding that heavily dilute other equity owners. The entire time I was covering it, nobody mentioned it except as a joke, meant to be ignored. You could bother building out all the debt waterfalls and convertible triggers, but all of that was wasted time.

After more experience though, you start to guess at the main metrics people are looking at, and spend more time building up a case on that. Sometimes it’d be company earnings guidance, sometimes actual business line performance, sometimes how they addressed a new regulation. I wish I’d built an even bigger network of China coverage investment analysts to chat names with before earnings.

With the above in mind, when comparing US growth investing to China growth investing, I felt that even fewer things mattered. However, the key drivers would be less well known and not as much public knowledge, unless you were in the right China groups. For example, on the fundamental investing side, the macroeconomic data usually didn’t matter. I’d get plenty of macro sell-side research, but it didn’t come up in the conversations I had with other analysts.

US names would have more data available (per point 1), more people closely analysing the numbers, and people more willing to pay a premium. As a result, China names tended to make larger price moves in reaction to a catalyst, since the information transfer was more piecemeal rather than gradual.

Lillian asked me if outsiders to China can generate alpha, and I suppose it depends on what outsider means. If we define an outsider as just looking at public data, not communicating with people living in China, and not visiting China (or something similar), I’d say no, you’re at too much of an information disadvantage.

Looking at public data for US names, you get up to speed quicker and know more about the company after your research compared to China names. For example, you might know 80% of what you need to know after 2 weeks for a US name, but only 50% of what you need to know after 3 weeks for a China name. And even then you probably missed the portion that people are actually caring about for now.

For example, one of the Chinese companies I covered would always give earnings guidance for its business segments, but only if someone asked for it. It became this ritual where every Q&A session someone would have to burn their question time to ask for this, which was probably the only set of metrics people really paid attention to. US companies would generally be more forthcoming with information, Chinese companies still needing to catch up on investor relations best practices.

If we define an outsider as someone not living in China, then I’d say yes, it’s possible, as long as you spend the time building that network mentioned above. At the time I was working, most firms covering China usually hired investment analysts born in China or who spoke the language, making it easier for them to get the network.

If that isn’t you, then you either need to visit China regularly or hound your existing friend group to get more introductions to people based in China. You probably also want to have a longer time horizon for your investment theses to play out vs US names. That’s been the case for the successful “outsiders” I’ve seen.

3. Don’t underestimate how quickly IPO sized companies can still grow

I consistently thought that companies would not grow as quickly as they did, that investors would be willing to pay that high of an earnings multiple, and that they would tolerate losses for only so long.

Many times these IPOing companies would have a similar story - They were IPOing to get more publicity and respectability. IPO proceeds were to be used to fund new business lines that were supposed to be the main driver of value in future years. You were essentially buying optionality at a high price.

Our team passed on many names that are now multi-baggers, because we felt that the valuation was too rich for the time. We should have been more risk-taking here and loosen our valuation criteria for good quality companies.

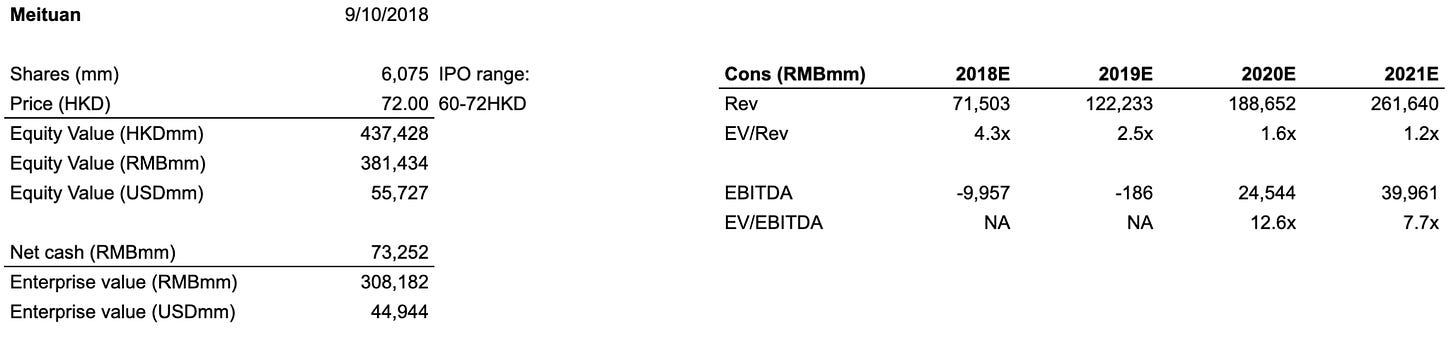

For example, we looked at Meituan (3690 HK) at the IPO, and modelled it to be 12-20x 2020E EBITDA, depending on the case:

Which made it too expensive for us, as outlined in part of the paraphrased investment thesis below:

Meituan is the leading player in food delivery, demonstrating the ability to gain share at the expense of Ele.me, their main competitor

We’re unable to make the math for a double (in stock price) work even under optimistic scenarios

Our Bull case Meituan trades at 15x 20202E EBITDA on food delivery alone, making it cheaper than comps but requiring flawless execution

We think Meituan is priced to perfection and will be passing on the IPO

Meituan’s EBITDA multiple is currently not meaningful8, and it trades at 6x revenue, even after all this time. We should have bought the business and focused less on the price.

Of course, there would be many IPOs that didn’t do as well - Uxin, China Literature, Huya for example. I believe these were all regulatory related but don’t quote me on that. However, after filtering out the lower quality businesses, the upside from cases like a Meituan seem to outweigh the downsides of a case like Uxin, just because of how much people are willing to pay for growth.

Reflecting on this now, it did seem like China tech investing was more venture capital-like in investing style, compared to US tech investing. You’d aim for bigger hits, have less information to work with, and the big wins covered your fund. The wins for US names tended to be a bit more evenly spread out.

Case studies

You should now have some idea of my previous firm’s investment style, so let’s look at two case studies, one which we called correctly, and one which we called wrongly. The numbers are from the time of the write up so they’re dated, but should be directionally correct.

In both cases, we’re looking at what to do with a stock going to IPO. Play along if you want extra credit. For extra, extra credit feel free to pull their prospectuses beforehand and come to a conclusion yourself (Xiaomi, BILI).

Case study 1: Xiaomi (1810 HK) IPOing Jul 2018

Business Overview:

Xiaomi is a low-end smartphone manufacturer with 8% of the global smartphone market, 14% of the China smartphone market and 27% of the Indian smartphone market.

70% of revenue is from smartphones, 20% of revenue is from other hardware (appliances, fitness trackers, etc), 10% from services (ads, payments).

The Xiaomi Services business takes advantage of the Android store being blocked in China, giving consumers a place to download ads and a payment platform.

The hardware business has 8% gross margins and low single-digit net margins. Xiaomi Services has ~ 60% gross margins and ~45-55% net margin. Smartphone sales drive services growth.

Thesis:

The bull case on Xiaomi uses the sum of the parts (SOTP) math and puts a high multiple on the high-margin services business (ads, app downloads, payments). Bulls believe Xiaomi will grow its services business as its low-margin handset business continues to scale.

We (my old firm) think investors are ignoring the fact that growth outside of China will come with lower services attach rate. The Android store is blocked in China, letting Xiaomi fill the void. However, outside China, Xiaomi must displace an Android Store with superior offerings and competitive advantages. We believe Xiaomi cannot scale its services business outside of China.

Thesis point 1: Xiaomi is the low-cost player in the global smartphone market. Their brand is viewed as the lower end. We don’t believe Xiaomi can take price and increase handset margins without losing share.

Thesis point 2: Xiaomi Services relies on smartphone buyers becoming Xiaomi Services users. We think Services growth decouples from smartphone growth as Xiaomi expands outside China and the Services business generates less profit than expected. The services business is only 10% of revenue but 40% of total gross profit and 80% of net income. For earnings to outperform Services growth must outpace smartphone growth.

And here are the financials we modelled:

What would your decision have been: Buy the IPO, short the IPO, or do nothing?

As might have been inferred from the tone of the language above, we were negative on the estimates that people were giving for Xiaomi, believing the numbers to be optimistic for an ok quality business. Contrast this to Meituan where we thought the business quality was good, but the price was high.

We did end up shorting Xiaomi after the IPO, which worked out well9:

And the story played out close to what we predicted. Xiaomi wasn’t able to scale hardware or software anywhere close to what their first projections were. This was a good short.

(Lillian note: For an update on Xiaomi and the uptick on their prices, it is a coming deep-dive for premium subscribers)

Case study 2: Bilibili (BILI) IPOing Mar 2018

Business overview:

Bilibili is an app for live streaming and regular user-generated video content (Lillian note: regular readers of CC will know Bilibili from this post and this deep-dive (paywalled). Content includes music performances, dance routines, tv show reviews, and humorous edited videos. It reminds me of Newgrounds back when it was popular. Bilibili started as an anime, comic, gaming content (ACG) site and claims to have changed since then to a full spectrum entertainment platform. I disagree since the popular content I saw (back in 2018) was still largely ACG related.

It monetizes via:

Gaming revenue from in-game item sales via games it distributes by targeting users (80%). 60% of total rev is from one hit game, Fate Grand Order. There are other games in the pipeline but they’re not close in popularity

Live streaming revenue from live streaming item donation rev share - ~10%

Mostly brand advertising types of ads, but management is looking to add performance-based advertising (pay for performance) to get more measurable metrics -~10%

Thesis:

60% of revenue is from one hit game, and their pipeline is unlikely to replicate that success. They claim they want to focus on ad revenue but I don’t think it’ll scale in time to make up for the game business.

Implied valuation is $2.9-3.6bn, which I think is very pricey for a niche site that is pitching a business transition from one single game to ad-supported. On 2021E NI of 467RMB mm and 20x P/E, equity value is only $1.5bn in an optimistic scenario.

And here are some modelled financials back in Q3 2017:

What would your decision have been: Buy the IPO, short the IPO, or do nothing?

We ended up doing nothing here. We lucked out in not shorting BILI, but definitely got it wrong still, as seen by how user and revenue growth just kept going:

Which continued to help people justify paying 8x sales for yet another company with a non-meaningful EBITDA multiple, and making a lot of money on the way:

If you’d asked me whether people would be easily willing to pay 8x sales I’d have been surprised10, and would have had to revise most of my model multiples upwards dramatically. BILI’s case was less obvious to me than Meituan’s since I had a lower opinion of the business, but clearly, I was wrong. This was a bad pass.

Lillian asked me if this was more of a difference between buying future growth vs continuation of the status quo, and I’d lean towards agreeing. The difference between China tech vs Western tech would be that you’d have to believe in more assumptions, and those assumptions would also be more aggressive.

If you were looking at a US tech name, it would be much easier to find management backgrounds, the main drivers of the stock would be more obvious to the investor community, and the growth rate assumptions less dramatic.

For China tech, you sometimes couldn’t find anything on whether the management team was a top-performing one, and you’d have to believe in the creation of entirely new business lines that were supposed to be the main driver of the stock three years down. Case in point, believing that a business like BILI would be able to manage that transition in the business mix. Many of the China tech IPOs all pitched a similar business transition story, unlike US tech which focused on strength of the core business line.

An investment fund that will buy (long) or sell (short) a company based on research and modelling done by their investment team

I’ve written here why investing is about relative, not absolute edge

Normally by a bank that has a client relationship with the company

Sell-side usually accompanies company management and arranges their IPO roadshow

You don’t own the company, you own a company that has a contract with the Chinese company

If Tencent invested in you pre-IPO and then didn’t buy more at the IPO, that would probably be a negative sign

To be fair, there are definitely cases where accounting fraud has become an issue of concern. For the most part, though investors take these risks as acceptable for the return

I get that some of you may feel EBITDA itself is non-meaningful but bear with me here. Feel free to insert your multiple of choice, it’d likely be the same takeaway

Note the axis here is cut off and not showing the most recent year, by which point we’d long covered the short

I’m still surprised now, and it’s difficult for me to figure out how people are making money buying stuff for double-digit sales multiples (besides just tossing a hot potato)

Bravo. An excellent article which I've shared with 3 people already... and probably counting. Thank you for sharing your insights and experience. It resonates so well with me as you've articulated exactly my experience, especially the one about taking a flying leap of faith.

thanks for sharing a very good article.